Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia: When Pain Gets Worse After Long-Term Opioid Use

Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Risk Calculator

Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Risk Assessment

This calculator estimates your risk of developing opioid-induced hyperalgesia based on key medical factors. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia is a condition where pain becomes more severe with increased opioid use.

It sounds impossible: you’re taking more opioids to control your pain, but it’s getting worse. Not just a little - a lot. The pain spreads. Light touches hurt. Your original injury or condition hasn’t changed, yet your body seems to be screaming louder than ever. This isn’t a mistake. It’s not weakness. It’s opioid-induced hyperalgesia - a real, measurable, and often misunderstood side effect of long-term opioid use.

What Exactly Is Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia?

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) is when your nervous system becomes more sensitive to pain because of opioids, not less. It’s the opposite of what you’d expect. Opioids are supposed to dull pain. Instead, after weeks or months of use, they can turn your nerves into overreacting alarms. Even gentle pressure, a breeze on your skin, or a routine movement can trigger sharp pain. This isn’t tolerance - where you need more drug to get the same effect. This is a new kind of pain, born from the drug itself.First noticed in rats back in 1971, OIH has since been confirmed in humans. Studies show that people on high-dose morphine, hydromorphone, or fentanyl - especially those with kidney problems - are most at risk. The pain doesn’t stay put. It spreads beyond the original injury site. A lower back pain might suddenly involve the hips, thighs, and even the feet. That’s a red flag.

How Is It Different From Tolerance?

Many doctors and patients confuse OIH with tolerance. They’re not the same.Tolerance means your body adapts to the opioid’s pain-relieving effect. You need a higher dose to get the same relief. But your pain level stays about the same - it doesn’t get worse.

OIH means your pain is actually intensifying. You take more opioids, and your pain gets worse. You might start feeling pain in places you never had it before. You might react painfully to things that never hurt before - like a bandage, a hug, or even a gentle touch.

One key sign of OIH is allodynia: pain from something that shouldn’t hurt. Cotton swabs, bed sheets, or a light breeze can trigger sharp, burning, or shooting pain. This is a hallmark of central nervous system sensitization - the same process seen in nerve damage and chronic neuropathic pain.

What Causes Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia?

It’s not one thing. It’s a cascade of changes inside your nervous system.The main culprit is the NMDA receptor. Opioids bind to their target receptors, but in doing so, they accidentally trigger a chain reaction that turns on NMDA receptors in your spinal cord. These receptors are like amplifiers for pain signals. Once they’re activated, they crank up the volume on everything your nerves send to your brain.

That triggers more release of glutamate - a key pain-signaling chemical - and less reuptake of it. Your brain and spinal cord get flooded. Pain pathways get rewired. Your pain threshold drops. Your tolerance for discomfort vanishes.

Other factors include:

- Dynorphin release: A natural brain chemical that, in excess, actually makes pain worse.

- Descending facilitation: Brain signals that normally suppress pain start promoting it instead.

- Toxic metabolites: Morphine breaks down into morphine-3-glucuronide, which can build up in people with kidney issues and directly irritate nerve cells.

- Genetics: People with certain versions of the COMT gene - which affects how your body handles stress chemicals like dopamine - are more likely to develop OIH.

This isn’t just theory. Animal studies show clear increases in pain sensitivity after morphine, heroin, and fentanyl exposure. Human studies using sensory testing confirm lower pain thresholds in patients on long-term opioids - even in areas far from their original injury.

Who’s at Risk?

OIH doesn’t happen to everyone. But certain patterns make it more likely:- High-dose opioids, especially intravenous or long-acting forms

- Long-term use - typically over 3-6 months

- Renal impairment (kidney problems) leading to metabolite buildup

- History of chronic pain conditions like fibromyalgia or neuropathy

- Genetic predisposition (low COMT enzyme activity)

- Recent surgery with high intraoperative opioid use

Studies estimate OIH affects between 2% and 10% of people on long-term opioid therapy. But because it’s often misdiagnosed, the real number could be higher. Many patients are told they just need more medication - when what they really need is a different approach.

How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no blood test. No scan. No single tool that confirms OIH. Diagnosis is clinical - meaning it’s based on patterns you and your doctor observe.Doctors look for:

- Pain worsening despite increasing opioid doses

- Pain spreading beyond the original area

- Allodynia or heightened sensitivity to non-painful stimuli

- No new injury, infection, or disease progression explaining the change

It’s a process of elimination. Your doctor must rule out:

- New spinal or nerve damage

- Withdrawal symptoms (which can also cause pain)

- Psychological factors like depression or anxiety

- Progression of arthritis, cancer, or other conditions

Some clinics use quantitative sensory testing - applying controlled heat, pressure, or touch to measure pain thresholds. If your pain threshold has dropped significantly in areas unrelated to your original condition, that’s strong evidence for OIH.

But here’s the hard truth: Only about 35% of pain specialists feel confident diagnosing OIH. Many cases go unnoticed - or worse, misdiagnosed as addiction or non-compliance.

What Can Be Done About It?

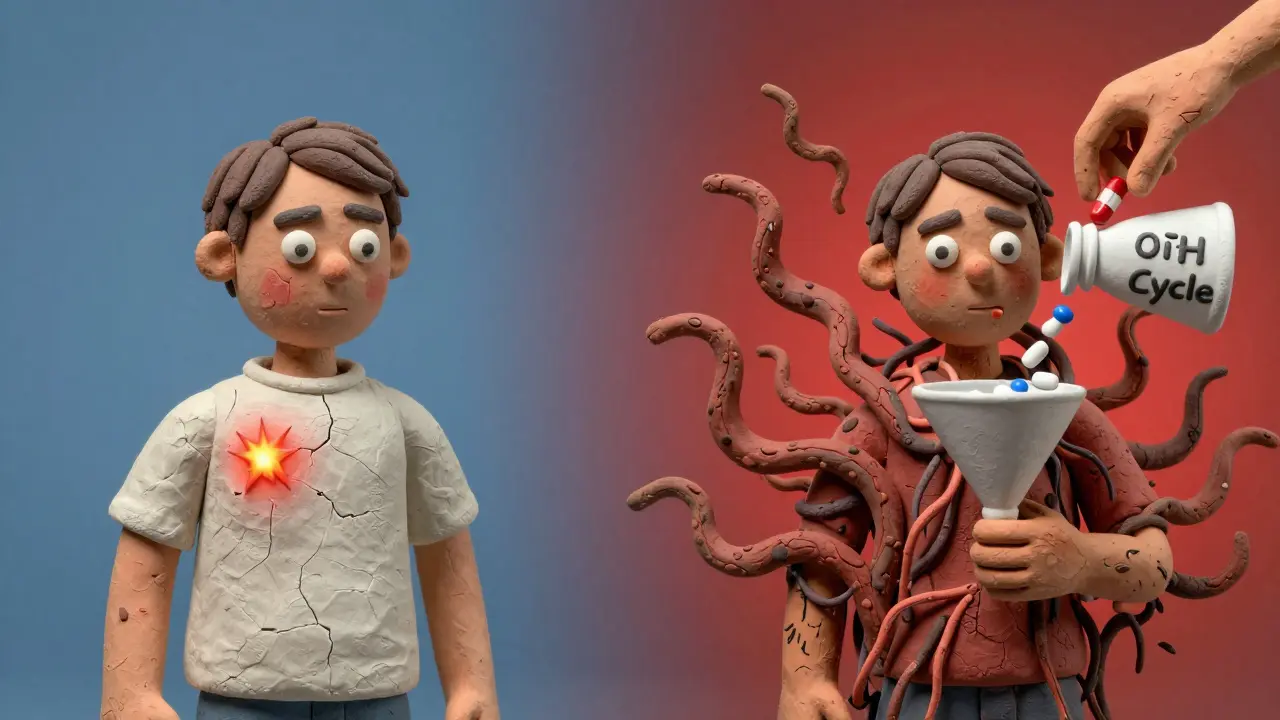

The good news? OIH can be reversed - but only if you stop the cycle.1. Reduce the opioid dose

This sounds backwards. If you’re in more pain, why take less? But because OIH is caused by the opioid itself, lowering the dose can actually reduce the pain. Think of it like turning down a volume knob that’s been cranked too high. Studies show patients often report less pain after a slow, controlled taper - even if they’re on less medication.

2. Switch opioids - try methadone

Methadone is unique. It works on opioid receptors like other opioids, but it also blocks NMDA receptors - the very ones driving OIH. That’s why switching to methadone often works better than just increasing the dose of morphine or oxycodone. One study showed patients who switched to methadone needed 40% less pain medication after surgery.

3. Add NMDA blockers

Drugs like ketamine (given in low doses) and magnesium sulfate can calm overactive NMDA receptors. These aren’t first-line treatments, but they’re powerful tools when OIH is confirmed. Ketamine infusions, for example, have helped patients who didn’t respond to anything else.

4. Use gabapentin or pregabalin

These drugs target calcium channels in nerves, which helps reduce the over-firing that happens in central sensitization. They’re commonly used for nerve pain - and they work well for OIH too. Typical doses range from 900-3600 mg/day for gabapentin, or 150-600 mg/day for pregabalin.

5. Non-drug approaches

Physical therapy, graded movement, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) help retrain your nervous system. They don’t cure OIH, but they help you rebuild tolerance to movement and touch. Many patients find that combining medication changes with therapy gives the best results.

Why This Matters - And Why It’s Controversial

Some experts still question how common OIH really is. They argue that what looks like OIH might just be uncontrolled pain, withdrawal, or psychological distress. And yes - those things can look the same.But the evidence is growing. Animal models are clear. Human sensory tests are consistent. And the clinical pattern - worsening pain with higher doses, spreading pain, allodynia - is too consistent to ignore.

Ignoring OIH leads to dangerous cycles: more drugs → more pain → more drugs. Patients end up on extremely high doses, with no relief. Some develop dependence, withdrawal symptoms, or even overdose.

Recognizing OIH changes everything. It shifts the goal from “more opioids” to “reset the nervous system.” It means stopping the harm, not just managing symptoms.

What Should You Do If You Suspect OIH?

If you’ve been on opioids for months and your pain is getting worse - especially if it’s spreading or triggered by light touch - talk to your doctor. Don’t assume it’s “just getting worse.” Ask:- Could this be opioid-induced hyperalgesia?

- Have we ruled out other causes of worsening pain?

- Would switching to methadone or adding gabapentin help?

- Can we try a slow, supervised dose reduction?

Don’t stop opioids cold turkey. That can trigger severe withdrawal. But don’t keep increasing the dose hoping it will help. That’s the trap.

Work with a pain specialist familiar with OIH. This isn’t something most general practitioners are trained to handle. You need someone who understands the neurobiology - not just the prescription pad.

There’s hope. OIH is reversible. Pain can improve. Sensitivity can decrease. But only if the right steps are taken - and early.

Can opioid-induced hyperalgesia happen after just a few weeks of use?

Yes, though it’s more common after several months. In some cases, especially with high-dose intravenous opioids or in people with kidney problems, OIH can develop within 2-4 weeks. It’s not just a long-term problem - it can show up faster than most expect.

Is opioid-induced hyperalgesia the same as addiction?

No. Addiction involves compulsive drug use despite harm, cravings, and loss of control. OIH is a biological change in how your nervous system processes pain. You can have OIH without being addicted, and you can be addicted without having OIH. But the two can happen together, which makes treatment more complex.

Can I still use opioids if I have OIH?

Sometimes, but only under strict control. Switching to methadone or adding NMDA blockers like ketamine may allow you to stay on lower opioid doses safely. In many cases, reducing or eliminating opioids leads to better pain control. The goal isn’t necessarily to stop opioids forever - it’s to stop the cycle that’s making your pain worse.

Does everyone on opioids get OIH?

No. Most people on opioids don’t develop it. But it’s not rare - studies suggest 2-10% of long-term users are affected. Risk goes up with higher doses, longer use, kidney issues, and certain genetic factors. If you’re on high-dose opioids for chronic pain, it’s worth asking about.

How long does it take to recover from OIH?

Recovery varies. Some patients notice improvement within days of reducing their dose. Others take weeks or months, especially if the nervous system has been sensitized for over a year. Combining dose reduction with gabapentin, physical therapy, and CBT can speed up recovery. Patience and consistency matter more than speed.

Are there any new treatments being developed for OIH?

Yes. Researchers are testing new NMDA receptor modulators and kappa-opioid receptor agonists that provide pain relief without triggering hyperalgesia. Some are exploring gene-based therapies to identify people at higher risk before they start opioids. While these are still in trials, they represent the next step in safer pain management.

Winni Victor

December 25, 2025 AT 17:57So let me get this straight - we’re telling people to take LESS of the very thing that’s supposed to fix their pain? That’s like telling someone with a broken leg to stop using crutches because the crutches are making the leg worse. I mean, sure, maybe the crutches are kinda dented and ugly, but I’m still trying to walk, you know?

Terry Free

December 26, 2025 AT 12:59Oh wow. Another ‘pharma shill’ article pretending to be science. OIH? More like ‘Opioid-Induced Hypochondria’. You people read one study and suddenly everyone’s got ‘central sensitization’ because they don’t want to quit their pain meds. Wake up. The real epidemic is people who think their pain is ‘neurological’ so they don’t have to do physical therapy or get a job.

And don’t get me started on ‘ketamine infusions’ - next you’ll be recommending ayahuasca and crystal healing. Classic pseudoscience dressed in lab coats.

Lindsay Hensel

December 26, 2025 AT 13:03This is one of the most compassionate, clinically grounded pieces I’ve read on chronic pain in years.

Thank you for naming what so many of us have felt but been told is ‘all in our heads.’ The spread of pain, the sensitivity to touch - I lived this for seven years. I was labeled ‘non-compliant’ until a pain specialist finally said, ‘This isn’t addiction. This is your nervous system screaming.’

It took two years to taper. It was hell. But I’m pain-free now. Not because I found a magic pill - because I stopped the poison that was making me worse.

Linda B.

December 26, 2025 AT 13:06Did you know the FDA approved opioids in the 90s after a single letter from a pharmaceutical exec saying they were safe? And now they want us to believe OIH is real? It’s not biology - it’s a cover-up. They don’t want to admit they poisoned millions so they invented a new diagnosis to keep the money flowing. Ketamine? Methadone? That’s just swapping one drug for another. The real solution is to burn down the entire medical-industrial complex and start over. They don’t want you to know this.

Also - your kidneys? They’re not broken. They’re being attacked by glyphosate in the water supply. That’s why metabolites build up. It’s not your fault. It’s the chemtrails.

Follow the money. Always follow the money.

Christopher King

December 27, 2025 AT 13:23Let’s go deeper. OIH isn’t just a biological phenomenon - it’s a metaphysical mirror. Every time you take an opioid, you’re not just numbing pain - you’re numbing your soul’s ability to feel truth. The pain spreads because your spirit is screaming to be heard. You think your nerves are firing? No. Your soul is crying out for meaning. You’ve been living in a system that commodifies suffering - and now your body is the protest.

So when you reduce the dose? You’re not just lowering a chemical - you’re lowering your resistance to existence. The real treatment? Meditation. Fasting. Disconnecting from the matrix. Ketamine? That’s just a gateway drug to enlightenment. I’ve been there. I’ve seen the void. And it’s beautiful.

Also - the government knows. They’ve been hiding this since 1971. They don’t want you to wake up.

They’re watching this comment right now.

Oluwatosin Ayodele

December 27, 2025 AT 15:18In Nigeria, we don’t have opioids like this. We have pain - real pain - from malaria, from bad roads, from no electricity. People die because they can’t get morphine. You’re talking about reducing opioids because they make pain worse? That’s a luxury problem. Here, we beg for a single pill. You don’t understand pain until you’ve had it and no one cares. Stop overcomplicating. If you have pain, take the medicine. If you die from it - then you die. Life is not a clinical trial.

Jason Jasper

December 27, 2025 AT 17:14I’ve been on opioids for five years after a car accident. My pain didn’t get worse - it plateaued. But I’ve seen friends who went from 20mg oxycodone to 120mg and still couldn’t sleep. One of them developed allodynia - even his socks hurt. He switched to methadone, tapered slowly, and now he’s back to hiking. It’s not easy. But it’s possible.

What helped most was finding a pain specialist who actually listened. Not the kind who scribbles scripts and says ‘take two and call me in a month.’ The kind who says, ‘Let’s figure out what’s really going on.’

It’s not about being weak. It’s about being smart.

Justin James

December 29, 2025 AT 08:56They’re lying. All of it. OIH is a myth created by the DEA to justify crackdowns on pain patients. Why? Because they don’t want people to know that opioids can be used safely for decades. The real problem? The media. The activists. The people who think every person on opioids is an addict. I’ve been on 60mg oxycodone for 14 years. I work full time. I raise two kids. My pain is controlled. My kidneys are fine. My COMT gene? Normal. So why am I being told I’m part of some epidemic? Because the narrative is more profitable than the truth. They want you scared. They want you to believe you’re broken. You’re not. You’re just being gaslit by a system that profits from your fear. And now they’ve invented a new diagnosis to make you feel guilty for surviving. Don’t fall for it. The real hyperalgesia is the fear they’ve implanted in you.

Zabihullah Saleh

December 29, 2025 AT 20:56There’s something beautiful about how the body fights back. We think medicine is about control - but sometimes, it’s about surrender.

Opioids were meant to be a bridge, not a home. But we turned them into a religion. We believed the promise: ‘This will fix you.’ And when it didn’t? We blamed ourselves. Or we blamed the drug. But maybe - just maybe - the pain was never the enemy. Maybe it was the silence we imposed on it.

Reducing opioids isn’t failure. It’s listening. And sometimes, the loudest thing you can do is stop taking something - and finally hear yourself.

Not all pain needs fixing. Some just needs holding.

Rick Kimberly

December 30, 2025 AT 11:06Thank you for this meticulously referenced, clinically nuanced overview. The distinction between tolerance and hyperalgesia is not merely academic - it is life-altering for patients who have been mismanaged for years.

I would add that the diagnostic challenge is compounded by the absence of standardized biomarkers. While quantitative sensory testing is ideal, it remains inaccessible to most primary care settings. We need point-of-care tools - perhaps even AI-driven symptom pattern recognition - to flag OIH early.

Furthermore, the genetic component (COMT) deserves greater attention in pre-prescription screening. Personalized pain medicine is no longer theoretical - it is imperative.

Sophie Stallkind

December 31, 2025 AT 04:21I am a nurse who has cared for patients on long-term opioids for over a decade. I have witnessed the slow unraveling - the increased dosing, the spreading pain, the tears during dressing changes because the gauze hurts.

I have also seen the miracle of tapering. One patient, after six months of gradual reduction, told me, ‘I didn’t realize I hadn’t felt grass under my feet in ten years.’

There is no shame in needing help. There is only shame in refusing to see when the help is hurting you.

Please, if you are reading this - talk to someone who understands. You are not alone.

Gary Hartung

January 1, 2026 AT 12:41Oh. My. GOD. Another one of these ‘I’m a victim of Big Pharma and my pain is too real’ sob stories. You know what else spreads? Cancer. And depression. And bad decisions. And people who think they’re special because they’re in pain. You’re not a martyr. You’re a statistic. And you’re probably just addicted and too lazy to get a real job or try yoga.

And ketamine? Please. That’s just a club drug with a prescription. You think you’re deep? You’re just high. Again.

Stop. Just stop. You’re not broken. You’re weak. And you’re making it harder for people who actually need opioids to get them.

Also - your ‘nervous system’? It’s not crying. It’s just being lazy. Get off the couch.

Ben Harris

January 2, 2026 AT 08:03They’re lying. They always lie. You think this is about pain? No. This is about control. OIH is just the latest tool to take away your meds. Why? Because they don’t want you feeling anything. They want you numb. But not with opioids - with antidepressants. With SSRIs. With therapy. With surveillance. With the system. The real hyperalgesia is the system making you feel guilty for needing relief. They don’t want you in control. They want you dependent. On them.

And the gene thing? COMT? That’s a lie too. Your DNA doesn’t decide your fate - the corporations do. They patented the gene. They own the test. They own the diagnosis. They own you.

Don’t trust the doctor. Don’t trust the science. Don’t trust the narrative. Trust your pain. It’s the only thing that’s never lied to you.

Mussin Machhour

January 3, 2026 AT 20:55Yo - I was on opioids for two years after back surgery. Pain got worse. I thought I was weak. Then I found a doc who knew about OIH. We cut my dose by 25% every two weeks. Took 8 months. I cried. I sweated. I wanted to quit. But now? I can pick up my kid without screaming. I can walk to the mailbox. I still have pain - but it’s mine again. Not the drug’s.

Don’t let anyone tell you you’re broken. You’re just learning how to heal.

And yes - gabapentin sucked at first. But it worked. You got this.