Multiple Drug Overdose: How to Manage Complex Medication Emergencies

What Happens When Someone Overdoses on Multiple Drugs?

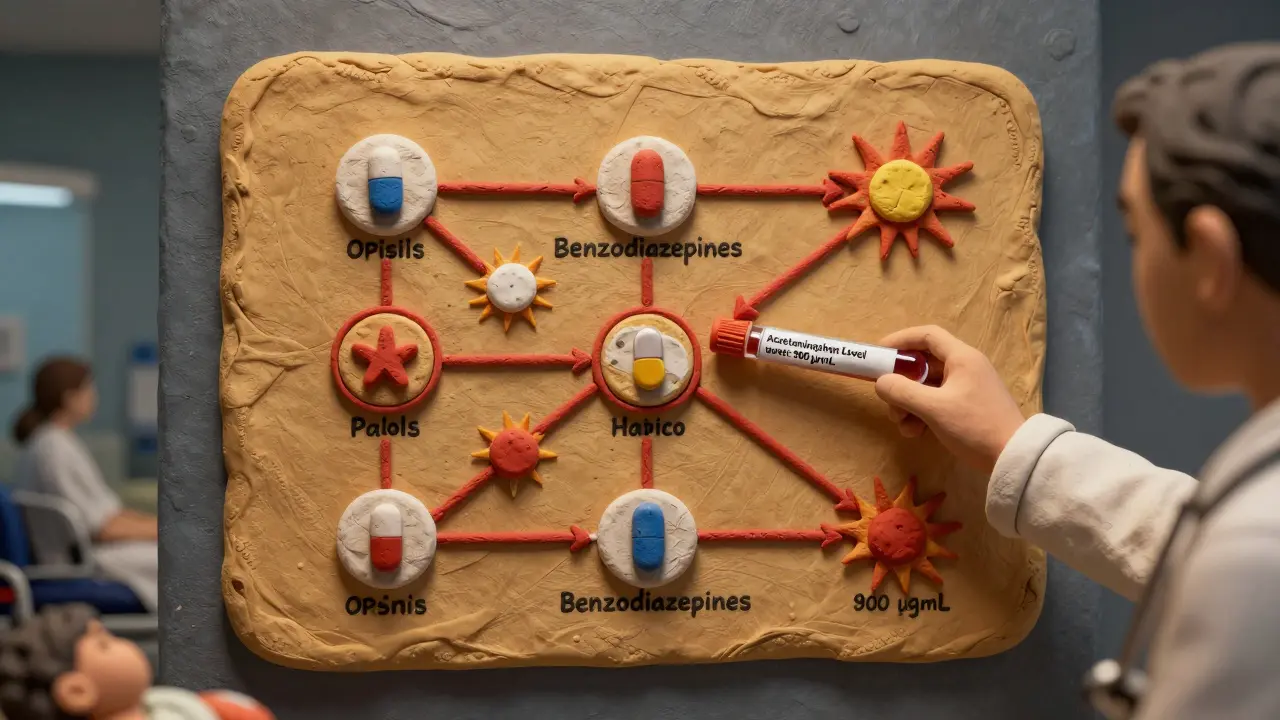

Most people think of an overdose as taking too much of one drug-like too many painkillers or a big hit of heroin. But in real life, it’s often worse. People don’t just take one thing. They mix opioids with benzodiazepines. They take prescription pain meds that already contain acetaminophen, then add alcohol or sleeping pills. This is called a multiple drug overdose, and it’s one of the most dangerous medical emergencies doctors face today.

It’s not just about the amount. It’s about how the drugs interact. Opioids slow your breathing. Acetaminophen destroys your liver. Benzodiazepines make you pass out. When they’re all in your system at once, the effects don’t just add up-they multiply. One drug can make another far more deadly. That’s why treating a single-drug overdose is simple compared to a mixed-drug one.

Why Standard Overdose Protocols Often Fail

First responders are trained to give naloxone for suspected opioid overdoses. That’s good. But if the person also took a massive amount of acetaminophen-say, from 20 Vicodin pills-naloxone will wake them up, but their liver will keep dying. If you stop monitoring after they breathe again, they could crash hours later from liver failure.

Or imagine someone took Xanax and fentanyl. Naloxone brings them back. But if you give flumazenil to reverse the Xanax, you risk triggering violent seizures because their body is dependent on both drugs. You can’t treat one without risking harm from the other.

That’s the core problem: the antidotes for one drug can make another problem worse. Many ERs still treat overdoses as if they’re dealing with one substance. That’s outdated. The 2023 JAMA Network Open consensus guidelines say clearly: when multiple drugs are involved, you manage them all at once.

Key Drugs in Multiple Overdoses and Their Specific Risks

Not all combinations are the same. Here are the most common and dangerous ones:

- Opioid + Acetaminophen (e.g., Vicodin, Percocet): This is the most frequent combo seen in ERs. The opioid causes respiratory arrest. The acetaminophen causes delayed liver failure. Naloxone works fast. Acetylcysteine takes hours to start protecting the liver. The window between waking up and crashing is narrow.

- Opioid + Benzodiazepine (e.g., heroin + Xanax): This pair is deadly because both depress breathing. Naloxone helps, but if the person is dependent on benzodiazepines, giving flumazenil to reverse it can cause seizures. Sometimes, the safest move is to just support breathing and wait.

- Acetaminophen + Alcohol: Alcohol makes acetaminophen far more toxic. Even a moderate dose becomes dangerous. Liver damage can start within 24 hours. Blood tests are critical.

- Tramadol + Other Depressants: Tramadol acts like an opioid but also affects serotonin. It needs higher or repeated naloxone doses because it lasts longer-up to six hours. Many people don’t realize tramadol is an opioid at all.

Each combo needs a different playbook. You can’t guess. You need to know exactly what was taken, when, and how much.

What Emergency Teams Must Do-Step by Step

Here’s what actually works, based on the latest guidelines from SAMHSA, WHO, and JAMA Network Open:

- Assess and call for help immediately. Don’t wait. If someone is unresponsive, not breathing, or blue around the lips, assume it’s a multiple drug overdose until proven otherwise.

- Give naloxone right away. Even if you’re not sure opioids are involved. It’s safe. If there’s no opioid, it won’t hurt. If there is, it could save their life. Give one dose. If no response in 2-3 minutes, give another. Fentanyl overdoses often need three or more doses.

- Support breathing. Naloxone doesn’t work instantly. While waiting, give rescue breaths. This alone can prevent brain damage. Don’t assume the person is fine once they move.

- Check for acetaminophen exposure. If they took painkillers, sleep aids, or cold medicine, assume acetaminophen is involved. Get a blood test ASAP. Don’t wait for symptoms. Liver damage doesn’t show up until it’s too late.

- Start acetylcysteine if acetaminophen is confirmed. This is the only antidote for liver damage. Dosing is based on weight-but cap it at 100 kg. For people over 100 kg, you don’t give more. Giving extra doesn’t help and can cause side effects.

- Don’t use flumazenil unless absolutely necessary. If benzodiazepines are suspected, avoid flumazenil unless the person has no history of dependence. The seizure risk is real. Support breathing instead.

- Monitor for at least 6-12 hours. Naloxone wears off in 30-90 minutes. Opioids like fentanyl or methadone last much longer. Someone can wake up, feel fine, then slip back into respiratory arrest hours later.

Activated charcoal can help if the person took the drugs within the last hour. But it’s not always safe-especially if they’re vomiting or unconscious. It’s not a magic bullet.

What Hospitals Do Differently

Emergency departments now follow strict protocols for complex cases. Blood tests are non-negotiable: acetaminophen level, liver enzymes (AST/ALT), kidney function, and blood pH. If the acetaminophen level is above 900 μg/mL and the patient has acidosis or confusion, they need hemodialysis.

Here’s the catch: during dialysis, acetylcysteine must still be given at 12.5 mg/kg/hour. You can’t stop it just because they’re on the machine. The drug doesn’t get filtered out fast enough.

For repeated acetaminophen overdoses-like someone taking extra pills every day for a week-the rules change. If liver enzymes are elevated or the level is over 20 μg/mL, give acetylcysteine regardless of when the last dose was taken. Timing doesn’t matter as much as damage.

What Happens After the Emergency?

Surviving the overdose is only the first step. Many people who overdose on multiple drugs have underlying substance use disorders. The WHO says people released from prison are at highest risk-up to 100 times more likely to die in the first four weeks after release.

That’s why the best outcomes happen when emergency care leads to treatment. After stabilization, patients need:

- A full psychological evaluation

- Screening for opioid use disorder

- Connection to methadone or buprenorphine programs

- Follow-up with a primary care doctor to check for liver or kidney damage

One study showed that patients who got linked to long-term treatment after an overdose were 50% less likely to overdose again. Without it, most return to the same patterns.

What the Public Can Do

You don’t need to be a doctor to help. Naloxone is now available without a prescription in Australia, the U.S., and many other countries. Keep a kit in your car, your home, or your bag. If you see someone unresponsive, give naloxone. Call 000. Do chest compressions if needed.

Also, don’t assume someone is fine just because they woke up. Stay with them. Watch their breathing. Make sure they get to a hospital. Too many people die because they were “fine” for an hour, then crashed.

Why This Matters Now

Fentanyl has changed everything. It’s 50-100 times stronger than heroin. It’s mixed into pills that look like oxycodone. People think they’re taking one thing. They’re taking something deadlier. And it’s often mixed with other depressants-benzos, stimulants, even xylazine.

In 2023, acetaminophen overdose still caused over 56,000 ER visits in the U.S. alone. Opioid overdoses killed 120,000 people worldwide. These aren’t numbers. These are parents, siblings, friends. The tools to save them exist. But only if we treat multiple drug overdoses for what they are: complex medical emergencies that demand precision, not guesswork.

Final Thought

There’s no single fix. No miracle drug. No shortcut. Managing multiple drug overdoses means knowing the risks of each substance, how they interact, and having the discipline to treat them all at once. It’s not glamorous. It’s not easy. But it’s the only way to stop people from dying after they’ve been told they’re ‘out of danger.’

Kristina Felixita

January 9, 2026 AT 07:18also, acetaminophen + alcohol is a silent killer. my uncle thought 'just a few beers with his pain meds' was fine. he didn't make it to the hospital.

Ken Porter

January 9, 2026 AT 08:19Annette Robinson

January 10, 2026 AT 06:40It's not about blame. It's about knowing that liver damage doesn't scream. It whispers. And by the time it yells, it's too late.

We run acetaminophen levels on *everyone* who comes in with suspected OD now. Even if they swear they only took opioids. You'd be shocked how often they don't even realize they took acetaminophen.

christy lianto

January 11, 2026 AT 14:52And yes, naloxone saves lives-but it’s not a license to keep using. If you’re going to gamble with your body, at least know what’s in the pills you’re popping.

swati Thounaojam

January 12, 2026 AT 06:06Luke Crump

January 13, 2026 AT 18:58What if the real solution isn’t more antidotes-but less stigma? Less policing? Less fear?

People don’t overdose because they’re weak. They overdose because they’re desperate. And we’ve built a system that punishes desperation instead of healing it.

Joanna Brancewicz

January 13, 2026 AT 20:39Evan Smith

January 14, 2026 AT 02:58…what if i just… didn’t take them in the first place? just a thought.

Lois Li

January 14, 2026 AT 04:06So now I carry naloxone. I tell everyone I know to get one. I don’t care if you think it’s 'enabling.' I care that someone I love is still here because we acted.

If you’re reading this and you’re scared to ask for help? You’re not alone. Talk to someone. Even if it’s a stranger. Just don’t wait until it’s too late.

Prakash Sharma

January 15, 2026 AT 14:41Manish Kumar

January 17, 2026 AT 08:13When a liver fails, it doesn't ask if you're a veteran, a single mom, or a college student. It just stops.

Maybe the real tragedy isn't the overdose-it's that we've forgotten how to see the human behind the statistic. We treat the drug, not the person. And that's why the cycle never ends.

Aubrey Mallory

January 17, 2026 AT 16:43Here’s what actually works: connection. Not judgment. Not more pills. Not more jail. Someone sat with them after they woke up. Asked how they were *really* doing. Didn’t fix them. Just listened.

That’s the antidote we’re not giving. And it’s the one that saves lives long-term.