Indomethacin for Osteoarthritis: Benefits, Risks & Usage Guide

Indomethacin Dosage Calculator

Calculate Safe Dosage

Select pain severity and administration route to determine appropriate Indomethacin dosage. All dosing follows clinical guidelines from the article.

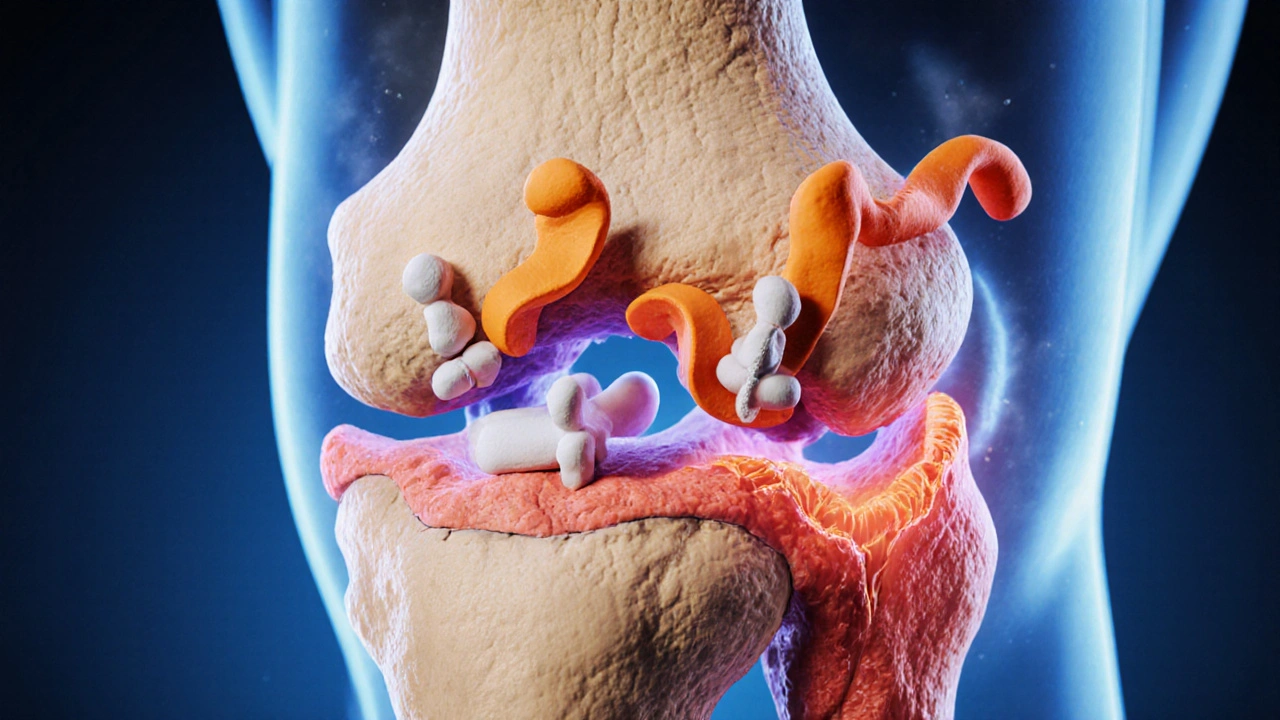

When doctors treat joint pain, Indomethacin is a non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drug (NSAID) that works by blocking enzymes involved in inflammation. It’s also known as Indocin and was first approved in 1965. Meanwhile, osteoarthritis is a degenerative joint disease characterized by cartilage loss, bone remodeling, and chronic pain. This review walks through how the drug acts, the evidence behind its use for joint disease, dosing options, safety concerns, and practical tips for clinicians and patients.

Mechanism of action: blocking pain pathways

Indomethacin belongs to the broader class of NSAIDs. The primary target is the cyclooxygenase enzymes (COX‑1 and COX‑2) that convert arachidonic acid into prostaglandins, which drive inflammation, fever, and pain. By inhibiting COX‑2 more strongly, Indomethacin reduces prostaglandin E2 levels in the joint space, dampening the sensitization of nerve endings that cause aching.

Because COX‑1 also regulates protective stomach lining and platelet function, the drug’s non‑selective nature can lead to unwanted effects. Understanding this trade‑off is key when prescribing it for osteoarthritis, a condition that often coexists with other comorbidities.

Clinical evidence for osteoarthritis pain relief

Randomized controlled trials from the 1990s onward have compared Indomethacin to placebo and other NSAIDs in knee and hip osteoarthritis. A 1998 meta‑analysis of six trials (total n≈1,200) reported an average 20‑mm reduction on a 100‑mm visual analogue scale (VAS) after two weeks of therapy, outperforming placebo by roughly 15 mm. More recent real‑world data from electronic health records (2022) show that patients who stay on the drug for at least four weeks experience a 30 % lower rate of escalation to opioid prescriptions.

However, the benefits tend to plateau after three months, and many clinicians rotate to agents with better gastrointestinal safety for long‑term management.

Dosage forms and recommended dosing

Indomethacin is available as oral tablets, capsules, and a topical gel. The oral route remains the most common for osteoarthritis because the gel’s penetration is limited to superficial joints.

- Standard oral dose: 25 mg three times daily (75 mg total) for mild‑to‑moderate pain.

- Maximum recommended dose: 150 mg per day, split into 3-4 doses, only for short‑term flare‑ups.

- Topical gel: 1% formulation applied to the affected joint twice daily; systemic absorption is <5 % of oral dose.

For patients with renal impairment, dosing should start at 12.5 mg twice daily and be titrated cautiously. Food can lessen stomach irritation but may also slightly delay absorption; taking the drug with a light snack is a pragmatic compromise.

Safety profile: what to watch for

Indomethacin’s efficacy comes with a well‑documented safety spectrum.

- Gastrointestinal bleeding - The most common serious adverse event. Risk rises with age, concomitant steroids, or a history of ulcers. Co‑prescribing a proton‑pump inhibitor (PPI) can reduce this risk by up to 60 %.

- Cardiovascular risk - Non‑selective NSAIDs can increase blood pressure and trigger thrombotic events. Patients with hypertension or prior myocardial infarction should be monitored weekly for the first month.

- Renal function - COX‑1 inhibition reduces renal prostaglandin synthesis, potentially lowering glomerular filtration rate. Baseline creatinine and periodic checks are advised for anyone on therapy longer than six weeks.

- Central nervous system effects - Dizziness or headache can appear, especially at higher doses. Advise patients not to operate heavy machinery until they know how they react.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifies Indomethacin as a prescription‑only medication, reflecting the need for professional oversight.

How Indomethacin stacks up against other NSAIDs

| Drug | Typical Dose | COX‑2 Selectivity | GI Bleed Risk | Cardiovascular Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indomethacin | 75 mg/day | Non‑selective (slight COX‑2 bias) | High | Moderate |

| Ibuprofen | 1200-2400 mg/day | Non‑selective | Medium | Low‑to‑moderate |

| Naproxen | 500-1000 mg/day | Non‑selective | Medium | Low |

| Diclofenac | 150 mg/day | Higher COX‑2 selectivity | Medium | High |

When short‑term, high‑potency relief is needed-such as after a flare-Indomethacin’s stronger COX‑2 inhibition can be advantageous. For chronic management, drugs with a better gastrointestinal profile (e.g., naproxen) are often preferred.

Practical tips for clinicians

- Screen for ulcer history, heart disease, and renal impairment before starting therapy.

- Consider a PPI (e.g., omeprazole 20 mg daily) for any patient over 60 or with prior GI events.

- Start at the lowest effective dose; reassess pain after two weeks.

- If pain control is inadequate, evaluate adherence and whether a topical formulation could complement the oral dose.

- Document a clear taper plan once symptoms improve to avoid unnecessary long‑term exposure.

Shared decision‑making improves adherence. Explain to patients why the drug may feel “stronger” than over‑the‑counter options and why monitoring matters.

Patient perspective: managing day‑to‑day use

Most people notice pain relief within 24-48 hours. However, taking the medication with food, staying hydrated, and avoiding alcohol can minimize stomach upset. If dizziness occurs, standing up slowly and scheduling doses at consistent times can help.

For those worried about long‑term effects, ask your doctor about rotating to a different NSAID or adding a disease‑modifying osteoarthritis drug (DMOAD) once evidence becomes available.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I use Indomethacin for knee osteoarthritis?

Yes, it is often prescribed for knee and hip osteoarthritis when rapid pain relief is needed. The usual oral dose is 25 mg three times daily, but a doctor will adjust based on your health profile.

How long is it safe to stay on Indomethacin?

Short‑term use (up to 4-6 weeks) is considered acceptable for most patients. Beyond that, the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and kidney problems rises, so your doctor should reassess the need for continuation.

Is the topical gel as effective as the oral tablet?

The gel works well for superficial joints like the finger or wrist, but it delivers only a fraction of the systemic dose. For deep‑joint pain (knee, hip) oral tablets remain more reliable.

Do I need a prescription to buy Indomethacin?

In the United States and most other countries, Indomethacin is prescription‑only because of its safety considerations. Online pharmacies that claim to sell it without a prescription are likely illegal.

What are alternatives if I can’t tolerate Indomethacin?

Common alternatives include naproxen, ibuprofen, or selective COX‑2 inhibitors such as celecoxib. Acetaminophen, intra‑articular steroid injections, and physical therapy are non‑drug options worth discussing.

Indomethacin remains a powerful tool in the osteoarthritis arsenal, but its use demands careful patient selection and vigilant monitoring. By weighing the pain‑relieving benefits against the gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risks, clinicians can tailor a regimen that keeps joints moving and patients comfortable.

Deja Scott

October 20, 2025 AT 19:10Indomethacin's efficacy can vary across populations, and clinicians should be mindful of cultural attitudes toward pain medication. While the drug offers rapid relief, many patients from communities that favor non‑pharmacologic approaches may be hesitant. It helps to discuss the risk‑benefit balance in a way that respects those perspectives. A shared decision‑making model often leads to better adherence and outcomes.

Demetri Huyler

October 26, 2025 AT 13:03Let’s be clear: the pharmacodynamics of Indomethacin are not just a footnote in a textbook, they’re a testament to American ingenuity in drug design. The COX‑2 selectivity gives us a punchy anti‑inflammatory punch without the fluff of some overseas alternatives. Of course, we still need to watch the gut, but that’s a small price for the power we wield. If you’re looking for a short‑term boost, this is the kind of NSAID that screams performance. Bottom line, for those of us who demand results, Indocin fits the bill.

JessicaAnn Sutton

November 1, 2025 AT 07:56Indomethacin, while pharmacologically robust, must be prescribed with an unwavering commitment to patient safety. The inhibition of cyclooxygenase pathways provides tangible analgesia, yet the concomitant suppression of protective prostaglandins imposes a moral duty upon the prescriber. It is incumbent upon clinicians to assess gastrointestinal risk factors before initiating therapy. A thorough medication reconciliation should reveal any concurrent NSAID use that could amplify adverse outcomes. The evidence base, as outlined in meta‑analyses, demonstrates modest pain reduction relative to placebo. However, the magnitude of benefit does not supersede the ethical imperative to minimize harm. Patients with a history of ulcer disease merit either gastro‑protective co‑therapy or an alternative agent. Moreover, the long‑term data suggest a plateau in efficacy after three months, reinforcing the need for periodic re‑evaluation. The clinician must therefore balance short‑term gains against potential chronic toxicity. Informed consent should encompass a discussion of both gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risks. Transparency in communication fosters trust, which is an essential component of therapeutic alliance. The prescriber’s responsibility extends beyond the prescription pad to include vigilant monitoring for signs of bleeding. Laboratory surveillance, when indicated, can preempt catastrophic events. Ultimately, the decision to employ Indomethacin should reflect a judicious appraisal of individual patient circumstances. When such deliberation is observed, the use of this potent NSAID can be ethically justified.

barnabas jacob

November 7, 2025 AT 02:50The pharmacokinetic profile of Indomethacin is characterised by rapid absorption and a high volume of distribution, which in lay terms means it gets into the joint quickly but also spreads systemically. From a mechanistic standpoint, COX‑1 inhibition can precipitate gastritic irritation, a side effect that is often downplayed in clinical notes. Clinicians should consider PPIs as a prophylactic adjunct, especially in patients with prior ulcer hx. Ignoring these nuances can lead to iatrogenic complications that erode patient trust.

jessie cole

November 12, 2025 AT 21:43When grappling with osteoarthritis pain, remember that you are not alone in this journey; many have walked the same path and emerged stronger. Indomethacin can offer a valuable bridge to relief, but it should be paired with physical therapy and lifestyle adjustments for lasting benefit. Start with the lowest effective dose and monitor for any stomach discomfort, adjusting as needed under medical guidance. Celebrate small victories, such as a decrease in pain score or increased joint mobility, as these milestones fuel long‑term progress. Your perseverance, combined with thoughtful medical support, will pave the way toward improved quality of life.

laura wood

November 18, 2025 AT 16:36I hear you on the cultural considerations, and it’s vital to listen actively to each patient’s narrative. By integrating their beliefs into the treatment plan, we can reduce resistance and improve adherence. This empathetic approach often translates into better outcomes and fewer adverse events.

Kate McKay

November 24, 2025 AT 11:30While the enthusiasm for performance is understandable, it’s equally important to temper that drive with caution. A stepwise titration can safeguard against sudden gastrointestinal upset. Encourage patients to report any early warning signs so adjustments can be made promptly. Open dialogue ensures that the pursuit of results does not compromise safety.

Israel Emory

November 30, 2025 AT 06:23Indeed, the ethical dimensions you outline are paramount, and they remind us that prescribing is more than a mechanical act, it is a moral dialogue, one that requires full disclosure of risks, benefits, and alternatives, plus a sincere invitation for the patient to voice concerns, thereby fostering a partnership built on trust, which ultimately enhances therapeutic success.

Andrew Hernandez

December 6, 2025 AT 01:16Indomethacin’s systemic reach demands caution especially for those with ulcer history. A PPI can mitigate risk. Keep monitoring.

Natalie Morgan

December 11, 2025 AT 20:10Your encouragement resonates, and it aligns with the evidence that multimodal management yields better outcomes. Maintaining motivation while adhering to low‑dose regimens can sustain improvements over time. Keep pushing forward, and remember that incremental gains add up.

Mahesh Upadhyay

December 17, 2025 AT 15:03The drama of pain management often feels like a thriller, yet the facts remain grounded. Indomethacin’s potency is undeniable, but the side‑effects script is equally intense. Patients deserve a clear plot twist: relief without catastrophe. Therefore, schedule regular check‑ins. Only then does the narrative end on a hopeful note.

Rajesh Myadam

December 23, 2025 AT 09:56I appreciate the balanced advice. Empathy paired with clear dosing guidance builds confidence. Let’s continue to support each other in navigating these therapies.

Alex Pegg

December 29, 2025 AT 04:50While the moral framework is essential, one must also recognize that some guidelines subtly favor pharmaceutical interests. This hidden agenda can shape prescribing patterns more than we admit. Skepticism is healthy, provided it does not devolve into cynicism. Critical appraisal keeps the profession honest.

Matthew Hall

January 3, 2026 AT 23:43Some think the drug is a miracle, but the shadows behind its side effects whisper louder than applause.

Kirsten Youtsey

January 9, 2026 AT 18:36It is apparent that the mainstream discourse on Indomethacin glosses over the covert alliances between pharmaceutical conglomerates and regulatory bodies. Such collusion subtly steers clinicians toward high‑risk regimens while downplaying gastrointestinal jeopardy. The lazy critiques offered in popular forums fail to interrogate these underlying power dynamics. A rigorous, independent review would likely expose the systematic bias embedded in current guidelines. Until that illumination occurs, prudence remains the only defensible course.