How Pharmacists Verify Generic Equivalence: Practice Standards

When a pharmacist hands you a pill bottle with a different name than what your doctor wrote, you might wonder: Is this really the same medicine? It’s not just a label swap. There’s a whole science and legal system behind it. Pharmacists don’t guess. They don’t rely on gut feeling. They follow strict, science-backed standards to make sure a generic drug is safe and effective as the brand-name version. This isn’t just procedure-it’s a critical safeguard in everyday healthcare.

The Foundation: What Makes a Generic Drug Equivalent?

Not all generics are created equal. To be approved, a generic drug must meet three clear criteria: pharmaceutical equivalence, bioequivalence, and therapeutic equivalence. Pharmaceutical equivalence means the generic has the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name drug. If your prescription is for 50 mg of metoprolol tartrate in a tablet, the generic must match that exactly.

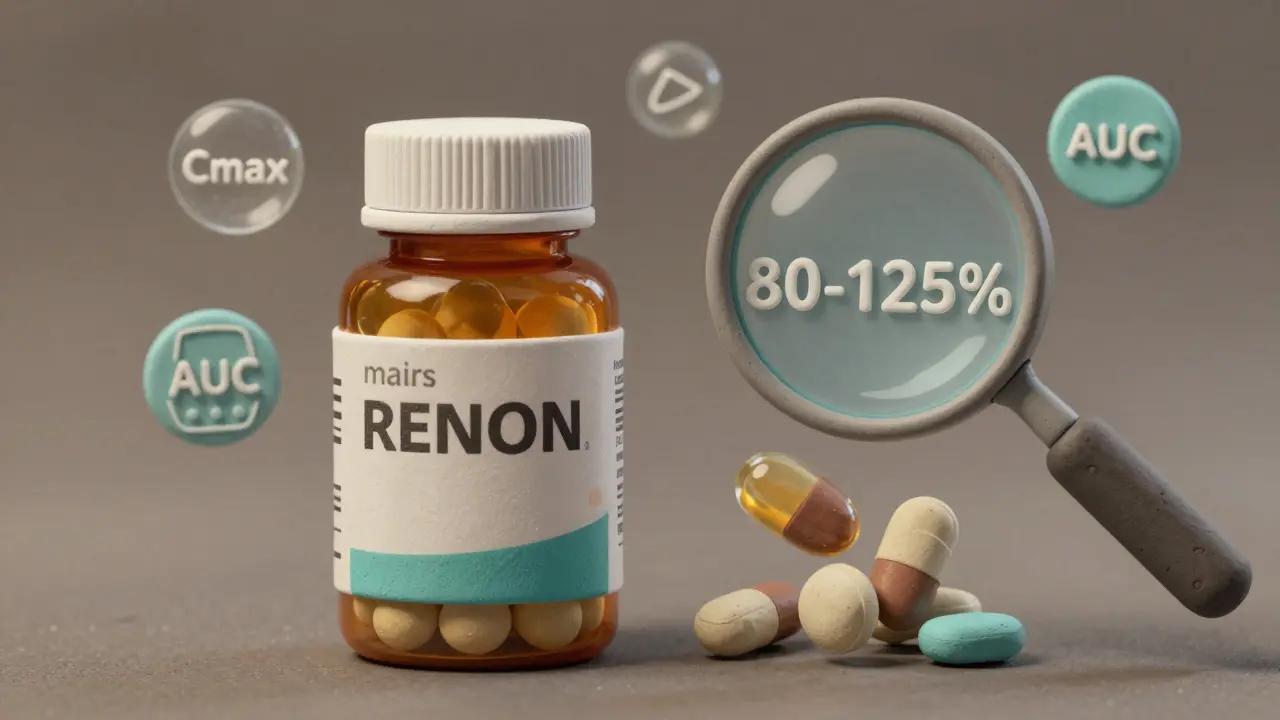

Bioequivalence is where things get technical. It’s not enough for the pill to look and taste the same-it must deliver the drug into your bloodstream at the same rate and amount. The FDA requires that the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of the generic to the brand drug’s maximum concentration (Cmax) and total exposure (AUC) must fall between 80% and 125%. In plain terms, the generic can’t deliver more than 25% more or less of the drug than the original. For high-risk drugs like warfarin or levothyroxine, the window tightens to 90-111% to prevent dangerous fluctuations.

Therapeutic equivalence is the final gate. It’s the FDA’s official judgment that the generic can be substituted without any expected difference in safety or effectiveness. This is where the Orange Book comes in.

The Orange Book: The Pharmacist’s Bible

The Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, better known as the Orange Book, is the single most important tool pharmacists use every day. Published by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration since 1980, it’s updated monthly and lists every approved drug with its therapeutic equivalence rating. As of April 2024, it includes over 16,500 drug products across 1,700 active ingredients.

The ratings are simple but powerful. A product gets a two-letter code. The first letter tells you if it’s therapeutically equivalent: A means yes, you can substitute it. B means no-don’t swap it. The second letter gives more detail. Most generics carry an AB rating, meaning they’ve passed both pharmaceutical and bioequivalence testing with human studies. You’ll also see codes like AN (aerosol), AO (oral solution), or AT (topical), which help pharmacists identify the drug’s form.

According to FDA data, 98.7% of rated products in the Orange Book are rated ‘A’. That’s over 15,900 drugs pharmacists can confidently substitute. In 2023, 90.7% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. were for generics-meaning this system is handling billions of doses every year.

How Pharmacists Verify Equivalence in Practice

When a prescription comes in for a brand-name drug, the pharmacist doesn’t just pull the cheapest option off the shelf. They follow a four-step verification process that takes 8 to 12 seconds per prescription:

- Identify the Reference Listed Drug (RLD)-the original brand drug-using the Orange Book’s database.

- Confirm identical active ingredient, strength, and dosage form-no deviations allowed.

- Check for an ‘A’ therapeutic equivalence rating-only ‘A’-rated products are legally substitutable.

- Look for a ‘Do Not Substitute’ flag-if the prescriber wrote it, the pharmacist must follow it, no matter what the Orange Book says.

Most community pharmacists use the free FDA Orange Book mobile app-downloaded over 450,000 times by March 2024. Others access it through pharmacy management systems like PioneerRx or QS/1. A 2023 survey of over 8,400 pharmacists showed 98.7% check the Orange Book daily. Only 62.7% use commercial databases like Micromedex or Lexicomp-and those are backups, not replacements.

Why? Because the Orange Book is the law. Every state except Massachusetts allows automatic substitution of ‘A’-rated generics, provided the prescriber hasn’t blocked it. Texas Administrative Code, California Pharmacy Practice Act, and New York Education Law all explicitly require pharmacists to use the Orange Book as the legal standard. In 2019, a Texas pharmacist was sanctioned for substituting a drug not listed in the Orange Book-despite claiming it was “equivalent.” The court sided with the law: only the Orange Book counts.

What Happens When a Drug Isn’t in the Orange Book?

Not every generic makes it into the Orange Book right away. About 5.7% of generic substitutions involve drugs that aren’t yet rated. This happens with newer products, complex formulations like inhalers or topical creams, or when the manufacturer hasn’t submitted the data. In these cases, pharmacists can’t just guess.

The FDA provides a framework called “Non-Orange Book Listed Drugs.” Pharmacists are trained to consult prescribing guidelines, manufacturer documentation, and peer-reviewed literature. They may contact the prescriber to confirm substitution is safe. Some pharmacists will dispense the brand-name drug if there’s any doubt. Professional judgment here isn’t optional-it’s mandatory.

Complex generics-like inhaled corticosteroids or topical ointments-are especially tricky. Traditional bioequivalence measures (blood levels) don’t always reflect how the drug works in the lungs or skin. The FDA has issued over 1,850 product-specific guidances for these cases, but many pharmacists still feel uncertain. That’s why training is critical.

Training, Accuracy, and Legal Protection

Pharmacist training on the Orange Book isn’t optional. The National Community Pharmacists Association reports that 92.4% of pharmacies require new hires to complete 2-4 hours of formal training on generic equivalence verification. Competency tests show that after training, pharmacists correctly verify equivalence 89.3% of the time.

That’s not just good practice-it’s legal protection. When a pharmacist follows the Orange Book, they’re shielded from liability under state substitution laws. If a patient has a bad reaction, and the pharmacist used the Orange Book correctly, the blame doesn’t fall on them. But if they substitute based on a commercial database or personal opinion? That’s malpractice territory.

Studies back this up. A 2023 analysis of 2,147 bioequivalence studies found that 97.8% of generics showed less than a 5% difference in total drug exposure (AUC) compared to brand-name drugs. The FDA’s 2020 meta-analysis showed the rate of adverse events after substitution was nearly identical: 0.78% for generics, 0.81% for brands. The difference? Statistically meaningless.

The Bigger Picture: Cost, Innovation, and Future Challenges

Generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $12.7 billion every year. In 2023, 8.9 billion prescriptions were filled with generics. Without the Orange Book’s clear standards, that savings wouldn’t be possible. Patients get the same medicine at a fraction of the cost. Pharmacies can stock more affordable options. Insurers pay less.

But the system is evolving. Biosimilars-complex biologic drugs that mimic expensive treatments like Humira or Enbrel-are now entering the market. As of June 2024, only 47 of 350 approved biosimilars are listed in the Purple Book, the biologics equivalent of the Orange Book. Pharmacists are now facing new questions: How do you verify equivalence for a drug made from living cells? Can blood levels even capture the full picture?

The FDA is responding. Through the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA) III, launched in 2023, $28.5 million is being invested in new bioequivalence methods for complex products. The Orange Book itself is being modernized for better digital integration with electronic health records.

For now, the system works. It’s transparent, science-based, and legally sound. Pharmacists aren’t just dispensing pills-they’re gatekeepers of patient safety. And every time they open the Orange Book, they’re doing more than checking a box. They’re ensuring that millions of people get the right medicine, every single time.

Can any generic drug be substituted for a brand-name drug?

No. Only generics with an ‘A’ therapeutic equivalence rating in the FDA’s Orange Book can be legally substituted. Drugs rated ‘B’ are not considered equivalent and must be dispensed as prescribed. Even if two drugs have the same active ingredient, if one isn’t listed as ‘A’ in the Orange Book, substitution is not permitted under state law.

Why do some pharmacists still use commercial databases like Micromedex?

Commercial databases like Micromedex or Lexicomp are useful for quick lookups, drug interactions, or dosing info-but they’re not legal substitutes for the Orange Book. Pharmacists use them as secondary tools to confirm details, but the Orange Book is the only source that provides the legally recognized therapeutic equivalence rating. Relying on anything else for substitution decisions puts pharmacists at risk of liability.

Are generic drugs really as safe as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generics to meet the same strict standards for quality, strength, purity, and stability as brand-name drugs. A 2020 FDA analysis of over 1 million patient records found no meaningful difference in adverse event rates between brand and generic drugs. Studies show generic versions typically deliver the same amount of active ingredient within 5% of the brand, well within the acceptable bioequivalence range.

What happens if a prescriber writes “Do Not Substitute” on the prescription?

The pharmacist must dispense the brand-name drug exactly as written, even if a cheaper, Orange Book-listed generic is available. This is a legal requirement in all 50 states. The prescriber may have clinical reasons-like a patient’s sensitivity to inactive ingredients or previous adverse reactions-that make substitution risky. The pharmacist’s role is to follow the prescription, not override it.

How often is the Orange Book updated?

The FDA updates the Orange Book monthly with supplements and releases a full annual edition. New generic drugs are added as they’re approved, and ratings are revised if new data becomes available. Pharmacists are expected to use the most current version-whether through the FDA’s website, mobile app, or integrated pharmacy software-to ensure they’re making decisions based on the latest information.

What to Do If You’re Unsure About a Generic Substitute

If you’re a patient and you see a different name on your prescription bottle, ask your pharmacist: “Is this an FDA-approved generic with an ‘A’ rating?” They’re trained to explain it. If you’ve had a bad reaction to a generic before, tell your doctor and pharmacist. Some people are sensitive to inactive ingredients-like dyes or fillers-even if the active drug is identical.

For pharmacists, the message is clear: stick to the Orange Book. It’s not just the best tool-it’s the only one that protects you, your patients, and your license. In a world of fast-changing drugs and complex formulations, this system is the anchor. And for millions of people who rely on affordable medication every day, it’s the reason they can keep taking their pills without breaking the bank.

Adewumi Gbotemi

January 12, 2026 AT 11:18So cool to learn how much goes into just giving someone a pill. I always thought generics were just cheap copies, but now I see it’s science, not guesswork. Thanks for explaining it so simply.

My uncle takes blood pressure meds and never asked - now I’ll make sure he knows the pharmacist is doing the right thing.

Alfred Schmidt

January 14, 2026 AT 09:51Wait-so you’re telling me pharmacists don’t just pick the cheapest one?!?!?!!? I’ve been getting ripped off for YEARS!!!

My last prescription was $12 for the brand, $3 for the generic-and I thought the pharmacist was just trying to save me money. Turns out they were following the LAW??!!

Who the hell lets this system exist?? The FDA? The Orange Book? This is insane!!

And now I’m mad I didn’t know this sooner. I could’ve saved thousands!!

Priscilla Kraft

January 15, 2026 AT 02:08This was so well explained!! 🙌

I work in a pharmacy and I love that we have this system-it’s like having a cheat sheet for patient safety. The Orange Book is my best friend 😊

Also, I always tell patients: ‘It’s not about cost, it’s about confidence.’ And honestly? Most of them walk out relieved.

Also, biosimilars are the next frontier… I’m excited (and nervous!) for what’s coming next. 💉🩺

Vincent Clarizio

January 16, 2026 AT 11:27Let me just say this: the entire pharmaceutical industrial complex is built on a fragile illusion of equivalence, and yet we treat it like gospel.

Do you know what bioequivalence really means? It means the drug gets absorbed within 80–125% of the brand. That’s a 45% range! That’s not equivalence-that’s a gamble!

And then you have these so-called ‘A-rated’ drugs that are chemically identical but have different fillers-dyes, binders, coatings-some of which trigger allergies, depression, even migraines in sensitive people!

And the Orange Book? It’s a bureaucratic monument to corporate convenience. It doesn’t measure patient outcomes-it measures pharmacokinetic curves in healthy young men. What about elderly diabetics? Pregnant women? People on five other meds?

And yet, we glorify this system like it’s divine law. We’ve turned medicine into a spreadsheet. And we wonder why people are sick.

It’s not just about substitution-it’s about control. Who decides what ‘equivalent’ means? The FDA? The manufacturers? The insurance companies?

And we call this healthcare?

Wake up.

There’s no such thing as ‘the same drug’-only different versions of the same promise.

Roshan Joy

January 16, 2026 AT 17:26Great breakdown! I’ve been a pharmacist in India for 12 years, and we don’t have anything like the Orange Book here.

Most of the time, we rely on manufacturer data, experience, and sometimes just… trust.

It’s scary how inconsistent it is. I’ve seen generics that work great, and others that leave patients dizzy or nauseous.

I’m really impressed by how systematic this is in the US. Maybe we need something like this here too.

Thanks for sharing the details-it’s rare to see this explained so clearly.

Michael Patterson

January 17, 2026 AT 21:39Ok but like… if the FDA says it’s A-rated, why do some people still have bad reactions? I’ve seen it happen. My cousin went into the hospital after switching to a generic thyroid med. They said it was ‘equivalent’ but she was basically dying.

So either the science is wrong… or the system is broken. Pick one.

Also, typo: ‘pharmaceutical’ is spelled wrong in paragraph 3. Just sayin’. 🤓

Matthew Miller

January 18, 2026 AT 04:3598.7% A-rated? That’s a lie. The FDA’s own data shows that 1 in 6 generics have bioequivalence failures in post-market surveillance.

They don’t test real patients. They test 20 healthy college kids on a diet of ramen and caffeine.

And you call this ‘safeguard’? It’s a public health loophole.

Someone’s making billions off this scam. And you’re here praising it like it’s a miracle.

Wake up.

It’s not science. It’s profit.

Madhav Malhotra

January 19, 2026 AT 21:41Love this post! 🙏

Coming from India, I’ve seen how generics are used everywhere-but we don’t have the same oversight. It’s wild to see how structured this is in the US.

My dad takes blood pressure meds, and I always tell him: ‘If it’s not in the Orange Book, don’t risk it.’

Thanks for making this so clear. Maybe one day we’ll have something like this back home.

Priya Patel

January 21, 2026 AT 19:06My pharmacist just handed me a generic and I said ‘Wait, is this the same?’ and she smiled and said ‘Yep, Orange Book says A-rated!’

And I was like… oh. 😅

Thanks for making me feel less weird for asking.

Also… I’m crying a little. This is actually beautiful. 💛