Cirrhosis: Understanding Liver Scarring, Failure Risk, and Transplantation

When your liver starts to scar, it’s not just a minor glitch-it’s a silent countdown. Cirrhosis isn’t a single disease. It’s the end result of years of damage, where healthy liver tissue gets replaced by tough, fibrous scar tissue. This isn’t something that happens overnight. It creeps up, often without symptoms, until one day, your body can’t keep up anymore. By then, the damage is mostly permanent. But here’s the thing: if you catch it early, you can still stop it from getting worse. And if it’s too far gone, a liver transplant might be your only real chance.

What Exactly Is Cirrhosis?

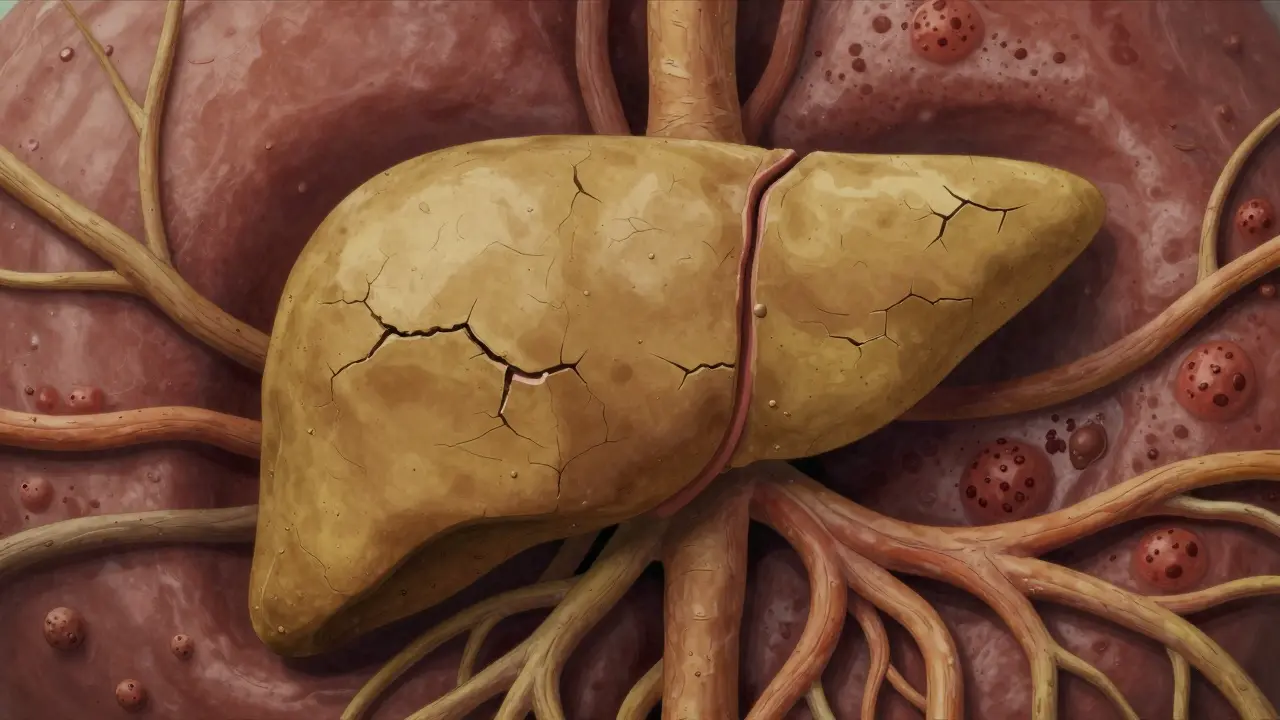

Cirrhosis means your liver has been battered for so long that it’s lost its ability to heal itself properly. Every time liver cells get injured-whether from alcohol, hepatitis, or fatty liver-they try to repair. But when the damage keeps coming, the repair job turns messy. Instead of healthy tissue, your liver builds thick bands of scar tissue. These scars don’t work. They don’t filter toxins. They don’t make proteins. They don’t produce bile. They just sit there, blocking blood flow and squeezing the life out of what’s left of your liver.

The term comes from the Greek word kirrhos, meaning tawny yellow-the color a damaged liver turns. That’s not just a description. It’s a warning sign. When doctors see that color on an ultrasound or biopsy, they know the liver’s structure has been rewritten. The normal lobules are gone. In their place are regenerative nodules, clumps of surviving liver cells trapped in a web of scar tissue. This isn’t inflammation anymore. It’s architecture collapse.

Compensated vs. Decompensated: The Critical Divide

Not all cirrhosis is the same. There are two stages-and the difference between them changes everything.

Compensated cirrhosis means your liver is scarred, but still managing to do the basics. You might feel fine. Your blood tests might be only slightly off. You could be walking around thinking you’re healthy. But inside, the damage is building. Up to 80% of people with compensated cirrhosis can live for years without major problems-if they stop the damage.

Decompensated cirrhosis is when the liver finally gives out. This is where symptoms crash in: fluid swelling in the belly (ascites), yellow skin (jaundice), confusion or memory loss (hepatic encephalopathy), vomiting blood from burst veins in the esophagus, and extreme fatigue. At this point, survival drops sharply. Five-year survival? It can fall to as low as 20%. That’s not a guess. That’s from data tracked by the American Liver Foundation.

The shift from compensated to decompensated is the point of no return for most treatments. Medications won’t reverse the scarring. Diet changes won’t fix it. Only a transplant can replace what’s broken.

What Causes Cirrhosis?

There’s no single cause. It’s the endgame for many long-term liver attacks:

- Alcohol: Still the #1 cause in many countries. Drinking heavily for 10+ years can trigger it. But even moderate drinking over decades can do damage.

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): Now the fastest-growing cause in the U.S. It’s tied to obesity, diabetes, and high cholesterol. About 24% of cirrhosis cases now come from this. And it’s rising fast.

- Hepatitis B and C: Chronic viral infections that silently destroy the liver over years. Hepatitis C, in particular, used to be a major driver-until antiviral drugs made it curable. But many people were diagnosed too late.

- Autoimmune hepatitis: Your immune system attacks your liver. Rare, but serious.

- Genetic conditions: Like hemochromatosis (too much iron) or Wilson’s disease (too much copper).

What’s changing? In the U.S., NAFLD has now overtaken alcohol as the leading cause. That’s a big shift. It means more people with no history of drinking are developing cirrhosis-often because they didn’t know they had fatty liver until it was too late.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Doctors don’t just guess. They piece together clues:

- Blood tests: High bilirubin, low albumin, high INR (clotting time), low platelets. These are red flags.

- Imaging: Ultrasound, CT, or MRI can show liver texture changes. But the real game-changer is elastography-a special ultrasound that measures liver stiffness. If it’s above 12.5 kPa, cirrhosis is very likely.

- Biopsy: Still the gold standard. A tiny sample of liver tissue shows exactly how much scar tissue is there. But it’s invasive. So now, many doctors rely on blood tests and elastography first.

- MELD score: This isn’t just a number. It’s your survival forecast. Based on bilirubin, creatinine, and INR, it ranges from 6 to 40. Higher score = higher risk of dying without a transplant. A score above 15 means you’re in serious danger.

Many people don’t find out until they’re already in trouble. A patient in Australia told me last year: “I had a routine check-up. My ALT was high. I thought it was from too much wine. Turns out, I had hepatitis C and cirrhosis. I had zero symptoms.” That’s the quiet horror of this disease.

Can It Be Reversed?

Here’s the hard truth: once cirrhosis sets in, the scar tissue doesn’t go away. No pill, no supplement, no miracle diet fixes it. But here’s the hope: you can stop it from getting worse.

If you have alcohol-related cirrhosis and stop drinking, your survival rate improves dramatically. If you have hepatitis C and get cured with antivirals, your liver can stabilize-even if it’s scarred. If you have fatty liver, losing 10% of your body weight can reduce scarring.

But once you hit decompensation? The damage is too deep. No treatment can reverse it. That’s why early detection matters so much. The goal isn’t to undo the scarring. It’s to keep it from killing you.

Liver Transplantation: The Last Option

When the liver fails, a transplant is the only cure. And it’s more common than you think. In the U.S., cirrhosis accounts for 40% of all liver transplants. In 2022, over 8,700 transplants were done. But there were 14,300 people on the waiting list. That means about 1 in 8 people die waiting.

Transplant isn’t a quick fix. It’s a massive surgery with lifelong consequences. You need to take anti-rejection drugs forever. You’re at higher risk for infections and cancer. But for many, it’s the difference between a slow death and a second chance.

New tech is helping. Normothermic machine perfusion keeps donor livers alive outside the body longer, making more organs usable. One 2023 study showed a 22% increase in transplantable livers using this method. That’s huge.

But the waitlist is still brutal. In rural areas, access to transplant centers is limited. In Australia, you might wait 6 to 18 months. In some parts of the U.S., it’s longer. And if your MELD score doesn’t rise fast enough, you might not make it to the top.

What Happens After a Transplant?

Recovery takes months. Fatigue lingers. Mental fog from past liver failure can take up to six months to clear. One Reddit user wrote: “I thought I’d feel normal after surgery. I didn’t. The brain fog was worse than the pain.”

You’ll need regular blood tests, doctor visits, and strict adherence to meds. But many people go back to work, travel, even play sports. The key is consistency. Skip a pill, and your body might reject the new liver.

Survival rates? About 75% live five years after transplant. Many live 20+ years. It’s not perfect. But for someone with end-stage cirrhosis, it’s the best shot they’ve got.

What About New Treatments?

There’s hope on the horizon. Researchers are testing drugs that target fibrosis directly. One drug, simtuzumab, showed a 30% reduction in scar tissue growth in early trials for fatty liver-related cirrhosis. It’s not approved yet, but it’s a sign we’re moving beyond just managing symptoms.

Stem cell therapies and bioartificial livers are also being tested. In one 2023 trial, patients with cirrhosis got infusions of lab-grown liver cells. Six months later, their MELD scores dropped by 40%. It’s early, but promising.

But here’s the catch: these aren’t replacements for transplants yet. They’re potential bridges-ways to keep people alive until a donor liver becomes available.

Living With Cirrhosis: Practical Steps

If you’ve been diagnosed, here’s what you need to do:

- Stop alcohol completely. No exceptions.

- Watch your sodium. Less than 2,000 mg a day. That means no processed food, no canned soups, no soy sauce.

- Get vaccinated. Hepatitis A and B. Flu. Pneumonia. Your immune system is weak.

- Monitor for warning signs. Swelling in legs or belly? Confusion? Dark urine? Yellow eyes? Call your doctor immediately.

- Work with a liver specialist. Not just a GP. A hepatologist. They know the protocols. They know the drugs. They know when to refer you for transplant.

And don’t ignore mental health. Depression is common. Fatigue is crushing. Support groups help. The American Liver Foundation’s nurse line (1-800-GO-LIVER) connects people with counselors and resources.

Final Thought: It’s Not Just About the Liver

Cirrhosis isn’t a liver problem. It’s a life problem. It affects your family, your job, your sleep, your mind. It’s expensive-average annual costs before transplant hit $38,000. After transplant? Around $350,000. Insurance helps, but not always enough.

But here’s what’s true: if you catch it early, you can live. If you act fast, you can avoid the worst. And if you need a transplant, the technology is better than ever. The challenge isn’t just medical. It’s awareness. It’s access. It’s breaking the silence around a disease that creeps up on people who think they’re fine.

Know your numbers. Get screened if you’re at risk. Don’t wait for symptoms. By then, it might be too late.

Can cirrhosis be reversed with diet and exercise?

Diet and exercise can help stop cirrhosis from getting worse-especially if it’s caused by fatty liver disease. Losing weight, cutting sugar, and avoiding alcohol can reduce liver inflammation and slow scarring. But once scar tissue has formed, it doesn’t disappear. No diet or supplement can undo advanced cirrhosis. The goal is prevention, not reversal.

How do I know if I have cirrhosis?

Many people have no symptoms until it’s advanced. Blood tests showing high liver enzymes, low platelets, or abnormal clotting can signal trouble. Imaging like ultrasound elastography can detect liver stiffness. If you have risk factors-like heavy drinking, obesity, hepatitis, or diabetes-ask your doctor for a liver screening. Don’t wait for jaundice or swelling to appear.

Is liver transplant the only cure for cirrhosis?

Yes, for end-stage cirrhosis. No medication can replace a failed liver. Transplant is the only treatment that restores full liver function. While new drugs and stem cell therapies are being tested, none are proven to cure cirrhosis yet. Transplant remains the only definitive solution for decompensated cirrhosis.

How long do people live with cirrhosis?

It depends on the stage. With compensated cirrhosis and no further damage, many live 10-15 years or more. Once it becomes decompensated, survival drops to 2-5 years without a transplant. The MELD score predicts risk: a score above 20 means less than 50% chance of surviving a year without a transplant. Early action saves lives.

Can you get cirrhosis without drinking alcohol?

Absolutely. In fact, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is now the leading cause of cirrhosis in the U.S. It’s linked to obesity, diabetes, and high cholesterol. Even people who never drink can develop severe scarring. This is why routine health checks matter-especially if you’re overweight or have metabolic syndrome.

What are the warning signs of liver failure?

Key signs include: swelling in the belly or legs, yellow skin or eyes, confusion or memory loss, extreme fatigue, vomiting blood, dark urine, and easy bruising. These mean the liver is no longer able to filter toxins or make essential proteins. If you have cirrhosis and notice any of these, seek emergency care immediately.

Elaine Douglass

December 20, 2025 AT 00:14Don’t wait for jaundice.

Takeysha Turnquest

December 21, 2025 AT 04:42Scarring isn’t failure. It’s a language. Are you listening?

Alex Curran

December 23, 2025 AT 04:05Elastography should be routine. Like cholesterol.

Dikshita Mehta

December 23, 2025 AT 16:10pascal pantel

December 24, 2025 AT 01:19Also, MELD score is garbage. It doesn’t account for age, comorbidities, or mental health. It’s a blunt instrument for a nuanced crisis.

Gloria Parraz

December 25, 2025 AT 06:12You can have cirrhosis and still go to work. Still laugh with your kids. Still feel normal. That’s the trap.

Get the bloodwork. Get the ultrasound. Don’t wait for your body to break down in front of you. You deserve to be healthy, not just surviving.

Sahil jassy

December 25, 2025 AT 11:35And yes, you can live 20+ years after transplant. I’ve seen it.

Kathryn Featherstone

December 25, 2025 AT 13:23We need better mental health support built into liver care. Not just as an afterthought.

Nicole Rutherford

December 26, 2025 AT 17:32If you’re overweight and have fatty liver, you’re not "trying your best." You’re playing Russian roulette with your organs. Stop romanticizing prevention. Just stop eating sugar.

Mark Able

December 27, 2025 AT 21:37Don’t be the person who says "I didn’t know." You knew. You just didn’t act.

William Storrs

December 28, 2025 AT 13:22You’re not behind. You’re just starting. And that’s enough.